Tea Time

Il se boit des hectolitres de thé dans les romans de Barbara Pym ; mais même à l’aune de cette consommation moyenne, Des femmes remarquables bat tous les records. Il ne se passe pas trois pages sans que quelqu’un ne mette la bouilloire sur le feu. Par cette insistance même, Pym s’amuse en sourdine de ce rite essentiel de la sociabilité anglaise. Or on ne plaisante pas avec ces choses-là, comme la narratrice en fait l’expérience dans les dernières pages du livre.

Sans doute passe-t-on trop de temps à préparer du thé, me dis-je en observant miss Statham qui remplissait la lourde théière. Nous avions tous dîné, ou du moins nous étions censés avoir dîné et nous nous réunissions pour discuter de la vente de charité de Noël. Avions-nous réellement besoin d’une tasse de thé ? J’allai même jusqu’à poser la question à miss Statham qui me renvoya un regard offusqué, presque scandalisé.

— Si nous avons besoin de thé ? répéta-t-elle. Mais, miss Lathbury…

Elle semblait abasourdie et profondément affligée. Je compris que ma question avait touché là un point essentiel et profondément ancré. C’était le genre de question susceptible de semer le désordre dans un esprit.

Je marmonnai que ce n’était là qu’une plaisanterie : il allait de soi que nous avions toujours besoin d’une tasse de thé, à toute heure du jour ou de la nuit.

Barbara Pym, Des femmes remarquables

(Excellent Women, 1952).

Traduction de Sabine Porte.

Julliard, 1990, rééd. Belfond, 2017.

Ubiquïté

Hal Wallis arriva sur les lieux à six heures et quart en compagnie de Richard Genero, dernier venu dans la brigade puisqu’on l’avait récemment promu du grade d’agent à celui d’inspecteur de troisième classe. Forbes et Phelps, les deux hommes de la Criminelle, étaient déjà là. Wallis prétendait qu’à la Criminelle, il n’y avait aucune différence entre un tandem de flics et et n’importe quel autre tandem de flics. Par exemple, il n’avait jamais vu Forbes et Phelps dans la même pièce que Monogham et Monroe. N’était-ce pas la preuve irréfutable que c’étaient les mêmes hommes ? De plus, Willis avait l’impression que tous les flics de la Criminelle échangeaient régulièrement leurs vêtements et que, quel que soit le jour, on pouvait fort bien trouver Forbes et Phelps vêtus des complets et manteaux de Monogham et Monroe.

Ed McBain, Tout le monde sont là

(Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here !, 1971).

Traduction de l’américain par M. Charvet

revue et augmentée par Pierre de Laubier.

87e District, vol. 4, Omnibus, 1999.

[Parfois, au détour d’un polar, une remarque incidente suggère le temps d’un éclair un autre roman possible. Ici, l’idée que tous les tandems d’inspecteurs ne sont en réalité qu’un tandem unique aurait pu inspirer une nouvelle fantastique à Borges ou au James de la Vie privée.]

Injustice

Deux ans après la mort de sa femme, Mr Vavasor fut nommé commissaire adjoint à un poste ministériel obscur traitant de liquidations judiciaires, qui fut supprimé trois ans après sa nomination. On crut tout d’abord qu’il conserverait les huit cents livres annuelles afférant à sa charge sans avoir rien à faire pour autant, mais la déplorable parcimonie du gouvernement Whig, selon les termes utilisés par Mr Vavasor lors d’une visite dans le Westmoreland pour décrire à son père les circonstances de l’arrangement subséquent, lui en interdit la possibilité. Il se vit offrir le choix d’accepter quatre cents livres pour ne rien faire, ou de conserver ses appointements actuels en assurant trois jours de présence hebdomadaire, à raison de trois heures par jour pendant la session parlementaire, dans une minable petite officine à proximité de Chancery Lane, où il aurait pour tâche d’apposer sa signature sur des fiches comptables qu’il ne vérifierait jamais et auxquelles il ne serait même pas censé jeter un coup d’œil. Il avait de mauvaise grâce choisi de garder l’intégralité de ses appointements et ces signatures constituaient depuis près de vingt ans l’unique tâche de son existence. Il se considérait bien entendu comme très injustement traité. Il envoyait, à chaque changement de ministère, d’innombrables requêtes au Lord Chancelier en place, le suppliant de mettre un terme à la cruauté de sa situation et de lui permettre de toucher son salaire sans être tenu de rien faire en contrepartie.

Anthony Trollope, Peut-on lui pardonner ?

(Can You Forgive Her ?, 1865).

Traduction de Claudine Richetin.

Albin Michel, 1998.

La transparence des choses

Lorsque nous nous concentrons sur un objet matériel, où qu’il se trouve, le seul fait d’y prêter attention peut nous amener à nous enfoncer involontairement dans son histoire. Les néophytes doivent apprendre à glisser au ras de la matière s’ils veulent qu’elle reste au niveau précis du moment. Transparence des choses, à travers lesquelles brille le passé !

Il est particulièrement difficile de ne pas crever la surface des objets donnés par la nature ou fabriqués par l’homme, objets inertes par essence, mais que la vie, insouciante, use beaucoup (vous évoquez, et fort justement, une pierre à flanc de coteau lestement foulée au cours d’innombrables saisons par des myriades de bestioles). Les néophytes s’enfoncent en fredonnant joyeusement et bientôt se délectent avec un ravissement puéril de l’histoire de cette pierre-ci, de cette bruyère-là. Je m’explique : un mince vernis de réalité immédiate recouvre la matière, naturelle ou fabriquée, et quiconque désire demeurer dans le présent, avec le présent, sur le présent, doit prendre garde de n’en pas briser la tension superficielle. Autrement, le faiseur de miracles inexpérimenté cesse de marcher sur les eaux pour descendre debout parmi les poissons ébahis. La suite dans un instant.

Vladimir Nabolov, la Transparence des choses

(Transparent Things, 1972).

Traduction de Donald Harper et Jean-Bernard Blandenier.

Fayard, 1979.

Rencontre au sommet

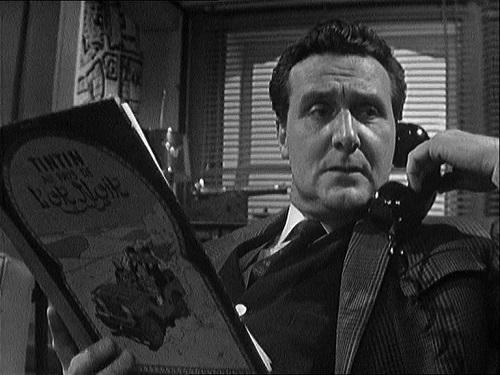

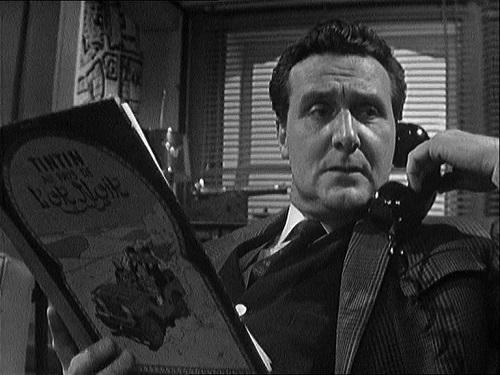

John Steed lit Tintin au Tibet : « A very bright little fellow », explique-t-il à un comparse. Cela se passe dans Man with Two Shadows (1963), l’un des bons épisodes de la période Cathy Gale.

***

Addendum (août 2020)

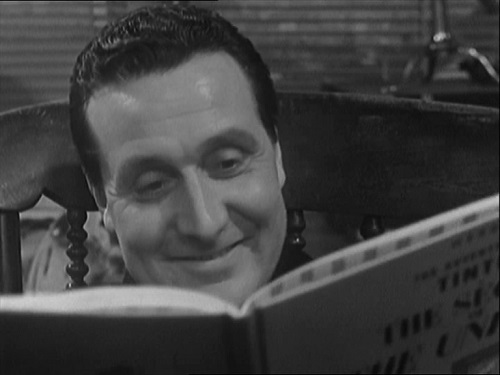

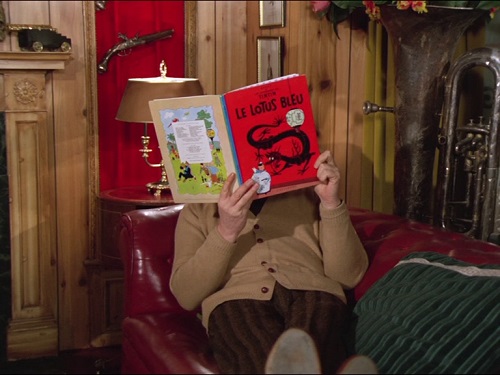

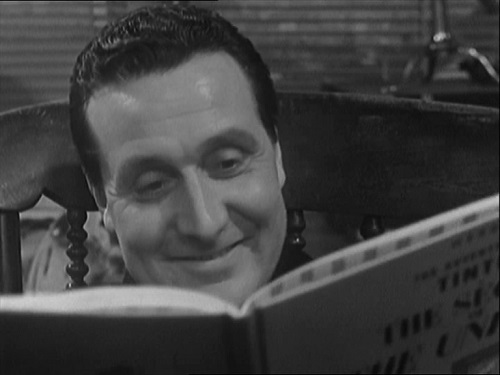

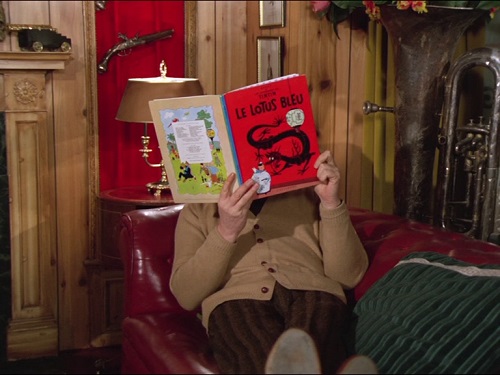

Comme le signale Hrundi V. Bakshi en commentaire, Steed lit à quatre reprises un album de Tintin dans The Avengers, tantôt en traduction anglaise, tantôt dans l’original français lorsque les albums n’avaient pas encore été traduits. « Blistering Barnacles ! » (« Mille sabords ! »), murmure-t-il même avec un sourire approbateur à la lecture de The Secret of the Unicorn. Les trois premières occurrences ont lieu en salve rapprochée durant la période Cathy Gale, la dernière quelques années plus tard durant la période Tara King. Captures d’écran ci-dessous.

À qui doit-on la persistance de cet hommage, sur six années, alors que l’équipe des producteurs et des scénaristes se renouvelait sans cesse ? À Patrick Macnee lui-même ? C’est un mystère. On n’a pas même trouvé la réponse dans l’ouvrage ultra-complet de fan maniaque de Michael Richardson, Bowler Hats and Kinky Boots (700 pages composées dans un petit corps, sans une illustration, Telos Publishing, 2014).

The Golden Fleece (1963)

The Outside-In Man (1964)

Look (Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One) but There Were These Two Fellers… (1968)

Voir, se voir (miroirs)

Giorgio Vigarello rattache la naissance du sentiment de soi à une nouvelle appréciation et sensation de son propre corps dans l’univers. Elle adviendrait à l’époque où la connaissance médicale et le savoir scientifique favorisent un retour juste sur soi-même, un jugement plein et complet.

La présence des objets y est pour beaucoup. Les limites physiques de notre corps se lisent en fonction des vêtements qui nous habillent, des meubles avec lesquels nous partageons notre espace de vie. […]

Au XVIIIe siècle, le miroir tient d’ailleurs une place inédite et peut être lu comme l’objet paradigmatique du thème traité ici. Dans la culture matérielle des Lumières, le miroir signale, par le réfléchissement, un nouvel être au monde. Il montre des individus entourés des objets qui participent de leur identité. […]

Objet de luxe parmi les plus chers, le miroir devient au fil des ans un objet que la bourgeoisie parvient à acquérir. Un siècle après sa naissance dans les appartements du roi à Versailles, il entre dans les maisons bourgeoises. Outre soi-même, le miroir de grandes dimensions est susceptible de réfléchir la personne accompagnée de ses objets. Là encore, il véhicule une représentation nouvelle de l’être dans son environnement matériel.

Cette image complexifiée désigne ce que j’entends par « intime ». Non un rapport uniquement personnel et confidentiel à soi-même, au sens d’une entité psychologique perçue de l’intérieur, mais un rapport étroit et quotidien avec soi et les autres, un rapport familier avec les objets […]. La relation qui s’instaure entre corporéité et culture matérielle est une clef pour comprendre le moment où l’homme commence à sentir les effets d’une liberté individuelle propre. Alors que l’optique scientifique a su corriger les défauts simples de la vue depuis le XVe siècle, c’est réellement au XVIIIe siècle qu’elle est admise. Le port des lunettes […] se généralise durant cette période. À partir d’objets comme l’éventail-lorgnette (un éventail pourvu d’un verre optique grossissant), Gianenrico Benasconi, dans son ouvrage sur les Objets portatifs au siècle des Lumières, montre que ces dispositifs mobiles véhiculent de nouveaux modes d’interaction sociale. La loupe sert à mieux voir, là où l’éventail permet de cacher son visage.

Anne Perrin Khelissa, Luxe intime. Essai sur notre lien

aux objets précieux. Éditions du CTHS, 2020.

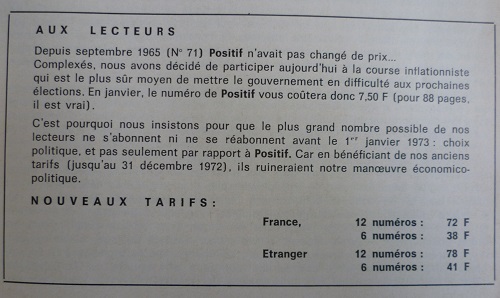

Augmentation des prix

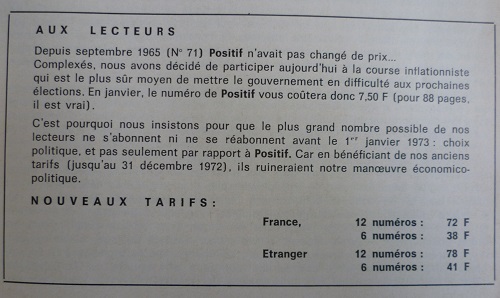

Positif n° 144-145, novembre, décembre 1972

En replongeant dans un vieux numéro de Positif pour y lire un dossier sur Charles Walters 1, on est tombé sur ce réjouissant encart. Peut-être faut-il y voir la patte d’Éric Losfeld, alors éditeur-gérant de la revue.

De nos jours, les revues ont tendance à communiquer sur le mode pleurnichard : «Excusez-nous d’augmenter nos prix, abonnez-vous pour assurer notre survie, à vot’bon cœur, messieurs-dames. » On nous permettra d’estimer que l’humour positiviste était plus propre à stimuler le réflexe d’abonnement chez les lecteurs.

1 Excellent ensemble consacré au quatrième mousquetaire de la comédie musicale à la MGM, comportant des études de Robert Benayoun et du regretté Michael Henry, un fort bon, rare et précieux entretien de Pierre Sauvage avec l’aimable Walters, une biofilmographie détaillée, ainsi qu’une étude du non moins regretté Michel Perez sur un corpus peu commenté, le musical avant Busby Berkeley.